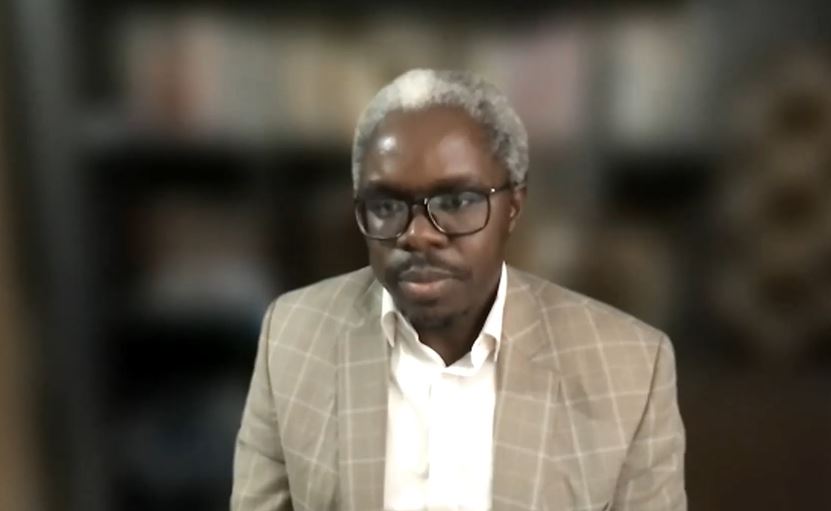

Dean Atwoli Shares Global Health Insights

The keynote presentation for the Midwest Universities for Global Health annual conference featured a provocative presentation by Lukoye Atwoli, MMed Psych, MBChB, PhD, discussing “COVID-19, Global Health and the Reification of Poverty.”

Professor Atwoli is the current dean of Aga Khan University Medical College of East Africa and former dean of the Moi University School of Medicine. He is a professor in psychiatry with extensive leadership, teaching and academic research experience.

“My aim today is to throw out some ideas around the issues that have been exposed by COVID-19 in the area of global health--thinking through some of the inequalities and inequities that have been exposed,” Professor Atwoli began. “The fact that COVID-19 is exposing this is an indictment on how we have designed the global health landscape up to this point.”

Professor Atwoli highlighted the reaction to initial low numbers of reported cases of COVID-19 in Africa. “Speculation immediately arose effectively purporting that poverty and broken-down health systems are protective against severe COVID-19 disease and death. But these speculations ignored the historical evidence that poorly organized health systems also collect data poorly. Therefore, they track morbidity and mortality poorly as well. And expecting that the coming of COVID-19 would suddenly improve how we collect our data and report on our health systems was, in my view, exposing certain attitudes that we have towards health systems in low and middle-income countries,” he continued.

“Even now, there's lots of effort being expended in trying to demonstrate an exceptionalism that effectively justifies the rife neglect and under-investment in health systems in low and middle-income countries,” Professor Atwoli continued, noting that the situation is reflected in poor and minority communities in the U.S. as well. “The challenge is universal, in my view, to ensure that all populations have access to high-quality evidence-based care rather than looking at the data that's coming out of these systems and trying to have any kind of deeper understanding of what that data means.”

Professor Atwoli said that global health is often associated with students and colleagues from wealthier countries creating healthcare solutions for low and middle-income countries. “Such solutions would often revolve around improvisation and cost-cutting, even in the context of health problems with proven solutions. The outcome of this is the institutionalization of what I refer to as ‘poor medicine for poor people’ on the assumption that poor populations shall never be wealthy enough to afford evidence-based health care,” he said.

“We have entire health systems built around the assumption that these populations will be forever poor and therefore, you have to design solutions that can only work in environments where majority of the people are poor,” he continued. “COVID-19 has exposed these inequities that underlie this global health paradigm and the need to ensure that even the poorest of the poor have access to quality health services if people in other settings are also to be protected. And global health, in my view, must now move to a new way of looking at things to denote an equitable partnership between institutions and communities of varied socioeconomic statuses aimed at generating truly global solutions to health problems that may present differently in different contexts.”

Professor Atwoli presented several examples from the COVID-19 pandemic where common global health practices such as task-shifting to lower-level providers and romanticizing traditional medicine, led to widespread disinformation and poor outcomes. He also emphasized that the inequitable distribution of commodities such as test kits and eventually vaccines is detrimental to all. “The emergence of variants that defy existing intervention is also evidence that had no corner of the planet is safe as long as another one has uncontrolled spread of a pathogen,” he said. “I think the lesson from this is that COVID-19 has demonstrated that there's only one global health system. The apartheid we have created can only serve to harm all of us.”

“If global health meant, truly global health or health equity, as we say, COVID-19 was our opportunity to demonstrate this. How it would've worked in my view, when vaccines came up, would be that we would have a criteria that is truly global in the sense that it identifies globally populations at high risk and prioritizes them to get vaccinated no matter where they are,” said Professor Atwoli, adding that age, pre-existing conditions, work circumstances and other factors are universally accepted as contributing to increased illness and death. “So COVID-19 was a perfect opportunity for us to truly demonstrates that global health is about health equity and it's about everybody having access to the health services that they need. Unfortunately, this was not the case.”

Professor Atwoli’s emphasis on equity extends beyond the current pandemic, however. “I think true partnerships in global health must firstly be based on equity. And therefore, whatever comes out of it must result in health solutions that are applicable in all geographies with that particular health problem,” he said. “You should follow the theme that solutions designed for problems in low, middle-income countries would find application in high-income countries and vice versa. The assumption in reciprocal innovation would be, that firstly, we all have something to learn from each other. But secondly, and perhaps more importantly, our health problems, at the core are fundamentally similar and would require similar approaches to solve them. The actual implementation can be tailored to locally acceptable methods, but the underlying principles in health interventions cannot vary so much based on the wealth of the community involved. And we think that if we build the concept of reciprocal innovation in this manner, it might ultimately replace some of the existing models of global health that are resulting in more harm than benefit for the populations in low and middle-income countries, but also in the high-income countries.”

Professor Atwoli’s full presentation as well as the thought-provoking question and answer session moderated by Hilary Kahn, PhD, associate vice-chancellor for International Affairs at IUPUI, and all of the presentation from the conference are available on the conference webpage.