Partnership is a critical element in any approach to research translation. Without effective partnership, researchers can be left without sufficient information on how to most effectively present findings or ensure studies are relevant to existing policy priorities. Involving those who can influence healthcare practice or policy early in the research process has shown to be a promising way for research to have impact.

Research suggests that as full partners, policy or practice stakeholders are more likely to feel a sense of ownership over research and ultimately utilize its outcomes (Georgeou and Hawksley 2020). Full partnership also mitigates traditional power dynamics on research projects between researchers and other collaborators, meaning that more extensive participation from policymakers could ensure more equitable and effective partnerships.

“Partnering with practitioners and policymakers can help researchers gain new insights into problems and advance the field with additional context,” said Christopher Rice, Research Translation & Policy Lead at the IU Center for Global Health Equity. “It also enables researchers to establish relationships with key influencers, collaborate on implementation ideas, expand opportunities for dissemination, and ultimately increase their research’s impact and relevance. Combining empirical evidence and rigor with practical, experience-based knowledge has a transformative power for both research and practice.”

Traditional research often saves the engagement of research end users for the end of the research process. As an example, a recent analysis of AMPATH Kenya investigators revealed that only 12.5% of respondents included county or national stakeholders as full researchers or investigators in the design, implementation, evaluation and translation of research. However, nearly 2/3 of respondents included external stakeholders as collaborators or to keep them informed, but not as full partners. Almost 19% did not include external stakeholders at all in research.

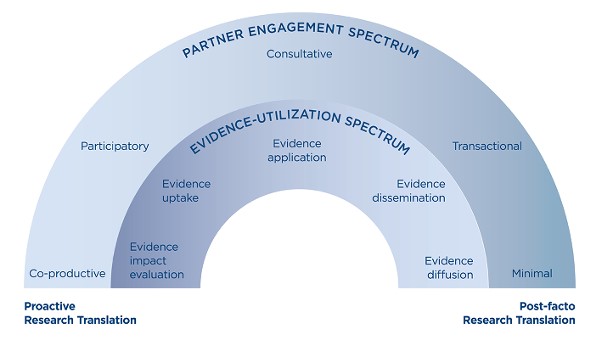

Engagements between researchers and policymakers do not always need to be full partnerships. It is sometimes not possible or even appropriate, such as in basic science or in funding where governments are limited as partners. Engagements can span from limited or consultative to participatory or co-productive and researchers and collaborators can determine what is most useful.

Rice formerly worked on the USAID-funded LASER PULSE project and noted the impact of involving outside collaborators. “At LASER PULSE, in our funding we required researchers and educational institutions to partner with at least one NGO, government organization, or private company,” he explained. “In some instances, the partner was the direct implementer of the research findings. In others, the partner served to advocate for changes in government. We found that those projects that adhered best to our model reported better research translation down the line.”

Researchers should consider partnerships that include county health officials, the Ministry of Health, local NGOs, clinical administrators or even companies. These partnerships can be characterized by shared decision making, proactive engagement, and two-way exchange, moving beyond just consulting or informing partners along the way. Practitioners can assist or lead the way in mapping out other stakeholders, setting up advisory committees, conducting planning and dissemination workshops, interpreting findings, and ultimately translating research into action.

Ultimately, involving practitioners and policymakers in healthcare research partnerships can help bridge the research to practice and policy gap; connect research questions to priority issues in government or clinical practice; create a sense of ownership and interest in research; and facilitate dissemination and uptake. Researchers should consider if involving a practitioner partner in research question identification, study co-design, data collection, data interpretation, and research use will be beneficial.

This is the second part in a series on research translation. To read our first part on research translation, please see What is Research Translation and Why is it Important? Watch for the next article about approaches toward engaging stakeholders as part of the research process.

For related readings, please see:

Georgalakis, James, and Pauline Rose. 2019. “Exploring Research-Policy Partnerships in International Development.” IDS Bulletin 50 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2019.103.

Georgeou, N., and C. Hawksley. 2020. “Enhancing Research Impact in International Development: A Practical Guide for Practitioners and Researchers.” https://rdinetwork.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ERIID_V8_DIGITAL.pdf

Hanley, Teresa, and Isabel Vogel. 2012. “Guide to Constructing Effective Partnerships.” https://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/effective-partnerships-report.pdf

Riddering, Laura, Alexandra Towns, and Priyanka Brunese. 2022. Guiding Questions to Plan for Research Translation: A workbook to develop a research translation strategy, an implementation plan, and a monitoring & evaluation plan for research impact in international development. West Lafayette, IN: LASER PULSE Consortium. Accessed at https://laserpulse.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ERT-Promising-Practices-2022.pdf