Traditional academic products such as abstracts, manuscripts, posters, and reports might not be the most effective way to communicate information that informs healthcare practice and policy.

Researchers are trained and incentivized to produce traditional materials after conducting a study and these research products are useful in the academic community to build careers, obtain tenure and advance the field. However, they are often overlooked when amending health policy or changing health practice.

Although applied research products such as policy briefs, guides, decision aids, or videos are often not incentivized within academic structures, they are increasingly in higher demand from funders. While researchers might be focused on theoretical frameworks, methodological rigor, and extensive results tables, those using the data in practice or policy are likely to want key findings, conclusions, or recommendations supported with data.

“Academic research has the reputation at times of being for its own good, and its results often ‘sit on the shelf’ for years before they’re used,” said Christopher Rice, research translation & policy lead at the IU Center for Global Health Equity.

Clinical research, implementation science, and other areas of applied research naturally move research closer to practice. However, researchers in these areas still tend to produce research products primarily for the academic community that are not accessible to those outside of the academic community.

Even with the growth of open-source publications, practitioners and policymakers are not always aware of or trained in accessing and searching databases. If a hospital executive officer or deputy minister does access a publication or abstract, its length, language, and/or structure can make consuming it a challenge.

To properly impact health practice and policy, researchers should consider engaging policy or practice stakeholders to produce research outputs in a format that is more easily utilized. Previous articles have detailed these approaches to partnering or engaging with stakeholders. Researchers can extend these approaches toward co-producing outputs that are more accessible and likely to be used.

The most common type of applied research product is a policy brief. Researchers can work with stakeholders to determine the most important information for a brief including: policy relevance, format, and recommendations for organizational action. The format of a brief or any written communication should ensure that results are easy to see and understand.

“Busy officials or administrators are not going to spend time with extensive background information or methodology, and they might be put off by academic terminology. They want results they can use, and if your results are interesting, then they might read more about the background,” continued Rice.

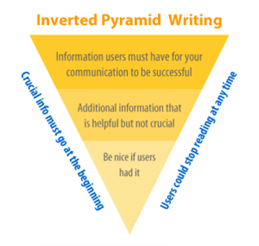

The optimal format for a policy brief or other research products runs contrary to how educational systems train investigators to write academic papers which is to start with background information, explain the methods, then results and conclusions. Instead, researchers should consider placing key findings and conclusions up front, adding details below, and additional context at the end or in a separate document. By focusing on the most necessary information, which could include a recommendation for an audience to take action, researchers increase the chance that the information is seen and used.

“The most effective policy briefs are tied to a specific health policy issue,” said Rice. “General informational briefs can only go so far if you do not tie your work to an ongoing issue. The key to an effective product is the connection between a potential change and a target audience to help affect that change.”

Language is another key consideration. Academia and health disciplines have specific terminology not understood by a lay audience. Writing in plain language increases accessibility to research and can help ensure it gets used. Researchers should create a few key messages about their research that are short, easy to understand and can be communicated verbally or in writing. Some of these messages could be recommendations for a practitioner or policymaker to take. These should be: feasible, one-sentence, start with an action verb, and specify who should take the recommended action.

Importantly, the product and its structure, content, and language need to be tied to an audience.

“Researchers have to think about their audience,” said Rice. “If you’re delivering a report with complex charts and p-values to community leadership, you might be missing the mark.”

Beyond briefs, researchers and their partners can consider developing a variety of other products, including:

- training guides

- videos

- podcasts

- media articles

- white papers

- operating manuals

- job aids or decision aids

- educational materials

- business plans

- physical infrastructure or gadget

- infographics

- data visualizations

Ultimately, while a policy brief or other product might seem like the natural end result of a study, a product is a small part of the overall research translation process. Researchers must strategize about dissemination and use, ideally at the start of a collaboration. Our next article will share effective methods to plan for dissemination and uptake.

Note: Research products can often refer to patent of innovation. This article focuses more on making findings accessible and useful.

Graphic source: https://www.umw.edu/web/fundamentals/site-content/writing-for-the-web/